R Scott Okamoto is “a writer, musician, and podcaster,” but his writing takes up this book review. His recent book, [INSERT LINK] Asian American Apostate, describes a weaving journey of his movement away from a personal religious faith, one characterized by evangelical Christianity, towards a recovery of his ethnic identity as Japanese American man, becoming welcomed into a pan-Asian community that he’d rarely known, and discovering satisfaction in his marriage, neighbors, and the arts. The journey recalls his youth, college days, and his movement out of graduate school into teaching in higher education, and while the weaving is good, the emphasis of his journey out of the Christian faith involves his discoveries as a lecturer in an English department.

Normally, such journeys would not make for exciting reading. It’s probably me: These autobiographical works of personal transformation stimulate my doing the eye-roll. It’s been awhile since I’ve read this genre; my faint memory of this reading is perhaps more due to the accumulated resistance to any narrative that likely omits encounters that would push back or forbid some personal victories or changes. You’re unlikely to find such omissions by Okamoto. He routinely observes some really weird and offensive stuff and keeps it real: Some of his changes emerge from making some social blunders or he simply omits confrontation with some genuinely wrong-headed and wrong-hearted people… of whom would be folks from within the evangelical Christian tradition… I found his book to be a real page-turner and there are some strong indictments of some Christian institutions that made Okamoto’s personal transparency all the more engaging, fallible, and a joy to read.

I’d heard (or read?) Okamoto stating he didn’t want the book to be a hit piece on the evangelical university (aka EVU) he taught at within the English department. But, if it weren’t for his reporting of the (can I say this Scott?) craziness at the institution, someone else would do it. Indeed, that reality is emerging and it renders the administration and the trustees (and, consequently, lumps in some faculty, students, and alumni) as racist, homophobic, decidedly Republican, and everything one might include in the adjective, “fundamentalist.” So, Okamoto’s book gives some authentic depictions of those realities, and more than once, I had to pause and wonder: How did these students get to EVU? What is happening at the family dinner table, Sunday mornings at their churches, and the kinds of social media these students are calling upon that would produce sexual/gender animus and casual remarks of hideous racial hostility in classroom discussions? It’s not merely that Okamoto had to endure these remarks: which is horrifying in itself. No, the absurdity of this institution goes much further: When he confronted such misguided thinking, he found himself having to explain his responses to his department chair! Coming after EVU would be low hanging fruit for Okamoto: He chooses to tell his story of faith deconstruction and how EVU and its participation within the larger evangelical movement contributed to his departure from the Christian faith.

It may help at this point to address something that, perhaps, you (and certainly for myself) wondered if there was some theological sticking point for Okamoto. In other words: What doctrinal matters became problematic for Okamoto and why? It’s a fair question, but that’s not how he rolls. So much of what he narrates falls squarely into a lived theology, one enacted by the late adolescents. I hasten to add: the label “lived theology” often signals participation in social justice movements that are informed by one’s faith tradition: You won’t find that embodiment among most of the students Okamoto describes.

Given the actors in the story, their sense of identity comes from what their parents and (male) pastors have inculcated in them. When the topic of sexual purity, viz., virginity, comes up in the classroom, Okamoto describes some genuinely naive and hilarious statements: “If you masturbate X number of times, you lose your virginity.” And: “Your virginity is the greatest gift you could ever give your spouse.” (187) Campus ministers will hear this kind of nonsense from students coming from the contemporary evangelical tradition: And they will make such assertions with a confident authority. It’s not unique or exceptional to EVU. This ersatz version of lived theology comes from pastors and youth directors that haven’t tried to test these statements against any close reading of the Bible or even within their own theological traditions. It’s like pulling teeth to even get such students to consider a thoughtful engagement with the Bible that would at least shed some light on sex: They are so confident what they know is secure, certain, and unassailable. That kind of theology was problematic for Okamoto, but it wasn’t something he was addressing.

I will add that the worship of money and the uncritical allegiance to the GOP also come in for interrogation by Okamoto. By and large, such criticisms are now well known. What makes his critique so interesting involves his awareness of how such commitments were well secured by even the first year EVU students in the late 90’s and were pervasive among the faculty. The EVU student body were overjoyed when McCain invited Palin on the 2008 GOP ticket: She was a Christian that they recognized. When Obama won the election, students were full of public anger and grief. Okamoto remained unsurprised when Trump was elected: The students and alumni had long been groomed for voting for such a candidate long before Obama became president. Most of what Okamoto describes is white Christian nationalism writ large much earlier than imagined and largely dismissed by most people. (Yes, including me.) He saw it early, often, and, to his credit, attempted to engage it with great questions. Even if some of his students did not change their minds, the vignettes of neo-con students that honestly took up Okamoto’s questions makes this reading compelling and gratifying.

What isn’t clear, though, is how these engagements within EVU moved or influenced Okamoto. I’m sure they had some influence, and he’s transparent about his revulsion about what is said and done at EVU. You’re likely to wonder as I did why did he stick around as a faculty member? He makes a few gestures towards a few responsive students that were often appalled by the lack of humility and compassion of their classmates. The early start of the Asian Pacific student group on campus gave Okamoto some encouragement but it soon became obvious that none of the leadership of the group would make some serious efforts to confront racism on campus. It wasn’t until some years later that Asian American students made some collaborative efforts with Black and Brown students on campus to publicly confront the highest levels of campus leadership, only to be stonewalled. Such movement over time developed good relationships for Okamoto; in such a context, his ongoing discovery of his ethnic identity received additional momentum.

And, this is where I would want my colleagues, InterVarsity staff, to pay attention here. The whole discussion of ethnic identity formation cannot be undertaken without considering how a person engages their faith, their experiences with racism, and their self-understanding of their ethnicity. While I want to encourage discoveries of family histories (which often account for migration stories) some of the social upheavals and cultural dynamics resist fixing our ethnic status. While many of us have routine encounters with racism that are structural in nature, we might presume that the constraints might be attempt to be color-blind. (They are not, but we know that.) Finally, the question of how we interrogate our faith often summons questions of ultimate concerns, agency, and community. These three measures become lifted by Okamoto in varying degrees, and while he narrates his journey as that of faith deconstruction, I would propose we also consider that he is also answering questions of what it means for him to be human. Those answers, given with authenticity and fallibility, contribute to his ethnic identity formation.

Okamoto provides several snippets of his undergraduate journey of faith while participating in InterVarsity at UC San Diego. He describes eating lunch with a couple of gay students and the mutual discovery that they could hold an amicable conversation. He doesn’t describe any serious conversations within his student fellowship about his being a Japanese American male, although such questions were already emerging. Later, while teaching at EVU, a family member invites him to a group of pan-Asian artists, and different questions emerge about the suitability of such gathering. Having identified this, Okamoto also realizes his sense of comfort and welcome by the others in the group. Meanwhile the sense of structural racism at EVU, throws his experiences with the pan-Asian artists into sharper relief. Being welcomed at EVU, even as the instructor of any number of courses, demands of him to concurrently surrender his ethnicity and to use conduct and speech that will comfort and welcome the white students, for whom any deviation from a particular ethnocultural system brings an immediate threat to their person. The students, after all, are the paying customers: Okamoto needs to be as unoffensive as possible, and to fulfill that need is an explicit denial of his ethnicity.

“But what about his faith?” Right: I wondered the same thing. To be fair to Okamoto, we shouldn’t expect him to offer a philosophical defense of his decision to leave the Christian faith: even less so to provide a theological apology. Here’s a guy who would lead worship as an undergrad in InterVarsity, and presents as a fairly chill participant in the evangelical tradition. It’s where he is confronted at UCSD by microaggressions or by how the formation of EVU fulfills an intention to serve a very small slice of Christian young adults who have little encounters with Jesus, Okamoto realizes how far such people are from the Jesus readily apparent in even the most lean and conservative reading of the Gospels. The vignette of the athlete discovering the spectrum of versions of Jesus riding a donkey discloses both the shallowness of the engagement of these students and the genuine respect Okamoto has for the Gospels as such stand. He doesn’t come out and say: “F this. I can’t stand these students-faculty-administrators-trustees who think Matthew 7:21-23 doesn’t address them.” He often has other versions!

This point is bit opaque: Okamoto isn’t departing the faith because of the racism directed toward him or the denial of his ethnicity or because his faith questions everything about EVU’s existence. But, it sure helps him observe the contrast between his developing community of artists and the degrading institution of EVU. The discovery of his emerging humanity from having a supportive family, neighbors, and the group of artists all contributed to his flourishing. Which I dare say: Most InterVarsity staff want this for their students and alumni, no? Granted, the conviction is that such would occur in the context of Christian community and a sense of mission: All of which were, by definition, absent wherever Okamoto turned. And goodness: He turned everywhere looking for such contexts and mission and none were to be found unless he gave up his ethnic identity and his ultimate concerns.

Which gets me here: Many of my present and former colleagues of InterVarsity have mentioned with a great deal of frustration, sadness, and disappointment: “So many of our students — especially the former leaders — can’t find a church that they can connect with or serve in in any meaningful way. Their faith is languishing.” Yes, and I’ve observed this: Even in myself. That our lives, our ethnic identities, and our faith development might wax and wane is not something that we address within our mentoring of university students. One might think the pandemic would have made such matters more explicit, but I don’t find that to be true in the present. For Okamoto, the kinds of strange stuff at EVU only tended to become reproduced at his local megachurch. Which he finally moved away from for a more mainline congregation: and that didn’t last either.

What Okamoto did discover was that community of pan-Asian artists continued to grow over the years and, more importantly, continued to welcome him and treat him as one of their own. He felt at ease, not having to defend his interests or what brought him joy. Such experiences lead him to conclude he had stopped believing in God, in Jesus, and the rest of the apparatus of the Christian faith: Okamoto renders this as apostasy. He continues to live a joyful life, one that has still engaged all of the suffering and disappointments that everyone breathing encounters. Okamoto now describes his life as “based on mutual respect and love for everyone around you for yourself…you gotta try this. Embracing my identity, my sexuality [he still identifies as a cis-hetero male], and my humanity has given me more joy, fulfillment, and sense of purpose than I ever had inside of Christianity.” If my InterVarsity colleagues and I are honest, the what and the how of our discipleship of students has produced others like Okamoto. Not that I agree with the assessment of Okamoto. Read on.

Some of my colleagues will recall in December of 2020 the cry of one of our own. The lament emerged from learning that an alumnus had reached out in distress. The former student expressed grief and confusion because he believed the presidential election had been stolen from Trump. The staff member asked how this alumnus could be so mistaken: That one of our own students could be misguided and upset that an election was now misrepresented as fraudulent. In a conversation with another colleague, I recalled this lament: “The way we mentor students worked perfectly.” The kinds of questions we asked then, even now, inadequately addressed politics, ethnic identity (although this has improved), or sexuality, or the kinds of social networks you rely upon for encouragement now and for your future.

To Okamoto and any other InterVarsity alumni: We failed to ask better questions of you. Even so, it’s good to get this out in front: There are ways to ask those questions that address what matters most to you. If in asking, “Who are the people that make you feel as though you have a present and a horizon with Jesus?” we’d also have to admit that we may not be that group. And, while we live in an “on-demand” culture, it’s not as though you could have turned instantly into a different church or community that would have welcomed you or loved you. If we shoulder some of the blame for failing to be as welcoming as the Gospel aims toward, it’s also true that we’re far more limited in knowing and trusting what is possible (or available) in Christian community.

For everyone, it’s worth recognizing that Okamoto does ascribe to evangelicals many of the woes and injustices toward women, non-White peoples, and the LGTBQIA communities. Where we are culpable, the faithful response is one of admission, of restitution, of reconciliation. (And, “No,” reconciliation is not some heartfelt express of sorrow and regret. It would take a much longer post to get into that!) But my point is that becoming responsible for setting things right where we have done wrong (yes, even if we were unaware of it) starts us in the right direction. Although I don’t consider myself an evangelical anymore (Christian, yes; evangelical, no), I know first-hand what kind of problems are generated by my former group. There are other ways to belong to Jesus and each other that do not involve the contemporary culture wars.

Finally, one might wonder if I expect Okamoto to return to Jesus and his church. It’s a fair question, and let me answer this in a layered way. I seriously doubt he would ever darken the door of any congregation that lives as those from EVU. I trust I don’t need to clarify this segment. But, I do sense that his self-disclosure of the kind of person he’s becoming will make him highly conscious and thoughtful about what community he would join in: One that self-consciously keeps itself from centering or protecting White people; an inclusive church that welcomes people of all ethnicities, genders, and social strata; a congregation that takes up sides with the poor and those suffering from injustice and violence and deprivation. There’s very few churches like these; I have a some other musings on this topic forthcoming.

Okamoto has stated he’s fine with the kind of person he’s becoming away from Jesus and his people. While I object to his broad-brush strokes in painting the evangelical faith, as though there were a single unified evangelical faith of whiteness, everything I’ve read so far makes sense to me: In other words, were any of us living in his shoes, all of the outcomes he describes should impress us as entirely plausible. It won’t come as a surprise that he has also marshaled some energies and relationships to explicitly oppose merciless evangelical influence in the world.

Lastly, I’m well aware of those encounters with Jesus that resist our efforts to hold him at a distance or keep him out of our lives. What I’m stating here is not that divine power overwhelms our agential powers or capacities. Rather, Jesus possesses those kinds of affection that enjoin our cognitive faculties to consider the source and whether we can remain open to him being the source of divine love. Such a Jesus, if I’ve read Okamoto correctly, welcomes everyone and invites them to join with him in making the world more just, more beautiful, more inclusive. Obviously, there’s much more to Jesus than this, but Okamoto is right, just spot-on, about how such a reading of Jesus won’t be found at EVU, and lead to the formation of Christian communities that live faithfully in response to that Jesus.

This self-talk can be both an experience of condemnation, confusion, as well as affirmation and clarity. Sometimes all of the elements present at once. I mention this, as

This self-talk can be both an experience of condemnation, confusion, as well as affirmation and clarity. Sometimes all of the elements present at once. I mention this, as  A friend in my office has moved from data collection to data analysis. One of his committee members, in listening to his early conversations regarding coding, suggested several textbooks, including

A friend in my office has moved from data collection to data analysis. One of his committee members, in listening to his early conversations regarding coding, suggested several textbooks, including

As is custom here, I make a comment or two on the birthday of the late, contemporary missiologist, Lesslie Newbigin. Most of my family, friends, and colleague know of my continuing indebtedness to Newbigin. Although I had not met the man, I sense that so much of his faith journey and understanding of mission overlapped with my own that I often sense in reading his works that he knows me better than I myself! To be sure, so much of Newbigin’s writings later in his life aimed at how mission might be directed toward the West.

As is custom here, I make a comment or two on the birthday of the late, contemporary missiologist, Lesslie Newbigin. Most of my family, friends, and colleague know of my continuing indebtedness to Newbigin. Although I had not met the man, I sense that so much of his faith journey and understanding of mission overlapped with my own that I often sense in reading his works that he knows me better than I myself! To be sure, so much of Newbigin’s writings later in his life aimed at how mission might be directed toward the West. So, when Netflix released a series from Marie Kondo, following on the success of her book,

So, when Netflix released a series from Marie Kondo, following on the success of her book,  Now, ever mindful that what comes to your mind and mine when we read/hear the word, “tidy,” Kondo then explains the breadth and depth of that activity. Not merely shuffling items around giving the appearance of order and doing so incrementally and routinely, for Kondo, to “tidy” has some depth to our possessions and household, procedures to excavate that depth, and practices to manage the depth of the possessions. From the book and the tv series, it becomes apparent that to “tidy” takes many days. The outcomes are remarkable. A few extra thoughts follow here regarding the notion of “spark joy,” some really, really good critiques of Western perceptions of Asian spirituality as a function of Kondo’s presence, and finally: books. Perhaps that is the one issue that everyone is polarized over.

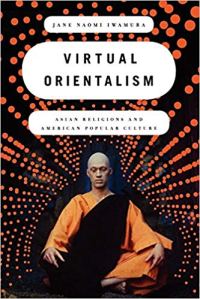

Now, ever mindful that what comes to your mind and mine when we read/hear the word, “tidy,” Kondo then explains the breadth and depth of that activity. Not merely shuffling items around giving the appearance of order and doing so incrementally and routinely, for Kondo, to “tidy” has some depth to our possessions and household, procedures to excavate that depth, and practices to manage the depth of the possessions. From the book and the tv series, it becomes apparent that to “tidy” takes many days. The outcomes are remarkable. A few extra thoughts follow here regarding the notion of “spark joy,” some really, really good critiques of Western perceptions of Asian spirituality as a function of Kondo’s presence, and finally: books. Perhaps that is the one issue that everyone is polarized over. Let me address everyone on the spirituality matter by referring you to my colleague,

Let me address everyone on the spirituality matter by referring you to my colleague,

You must be logged in to post a comment.